Off the Beaten Track 7 - In search of soapstone

Published: 15 May 2020

The Government have now agreed that we can go out to exercise more than once a day. That gives us more opportunities for visiting some of the archaeological sites which are all around us.

The Government have now agreed that we can go out to exercise more than once a day. That gives us more opportunities for visiting some of the archaeological sites which are all around us.

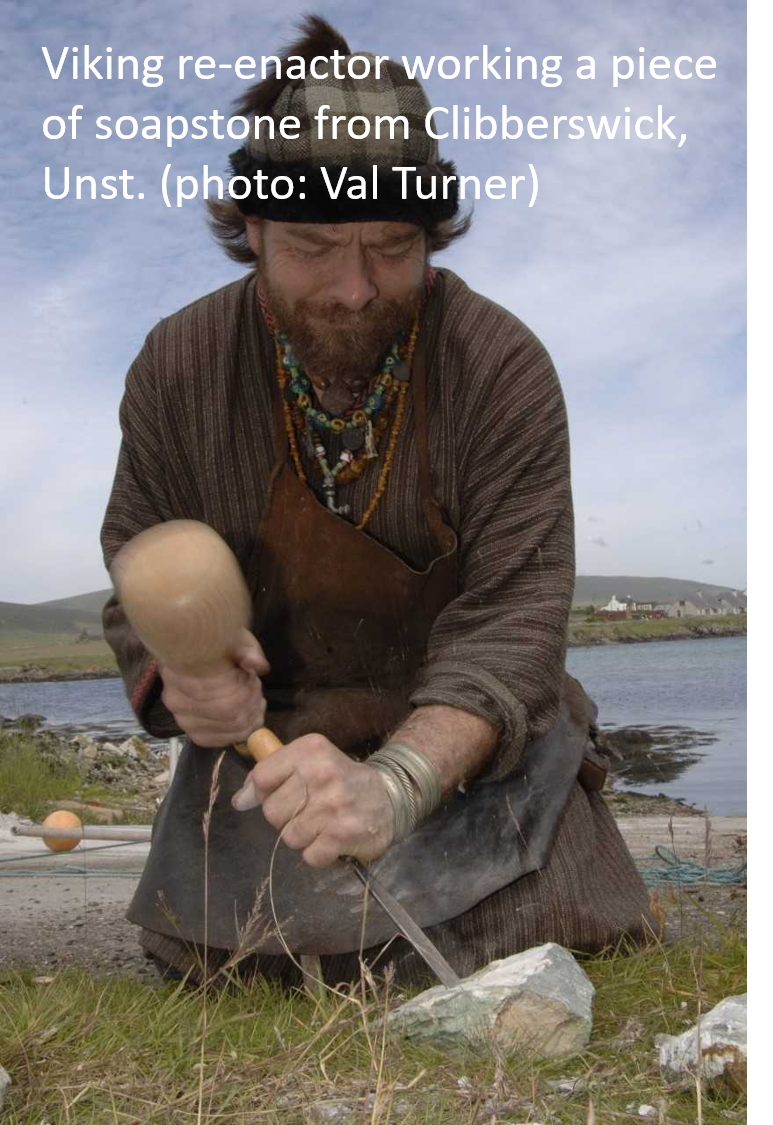

The walks this week take in Viking (and Norse) soapstone quarries. Soapstone is a form of steatite which is also known as talc. It is quarried commercially at Clibberswick, Unst as industrial talc, used for lubricating machinery and making fertiliser amongst other things. Shetland’s talc isn’t pure enough to become cosmetic talc.

Soapstone is so called because it has a very soapy texture and is so soft that, when it is fresh, it is possible to scratch it with your finger nail. It develops a hard crust (cortex) once it has been exposed and it has the almost magical property of hardening when heated.

This combination of factors made it very attractive to the Vikings for making pots (although these were extraordinarily heavy), bake-plates and smaller objects including lamps and loom-weights. Soapstone is known as “kleber” in Shetland dialect (with several variant spellings), derived from the Old Norse words for “loom weight stone” (klé) and “rock” (berg).

Shetland is one of the very few places in Britain where soapstone occurs and is one reason why the Vikings felt very at home here. However, soapstone was used from almost the beginning of settlement, beads made from it were found in both the Neolithic Sumburgh cist, and at the Scord of Brouster. Two large Bronze Age cremation urns found in Orkney must have been quarried in Shetland, and archaeologists recovered a collection of soapstone pots from a late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age house at Bayanne, Yell. Soapstone was used for fire bricks within living memory, but it was the Viking and Norse settlers who really knew its value.

Isbister to Fethaland (HU 371 909 – HU 377 944)

This walk will take the best part of a day, so go well equipped with lunch and prepared for the weather to change. Start at the point where the A970 ends at Isbister, North Roe. Take the right-hand (east) fork (not through the farmyard), pass a cottage and follow a rough track, crossing three fences using the stiles. From the third stile there is an excellent view of the Kame of Isbister.

Archaeologists think that this stack-top site was probably a Pictish monastery, although Andrew Jennings has recently suggested that it might be a Viking fort. Twenty-three small huts (about 6m x 3m) were built in two rows. The stack top is inaccessible to the general walker (I have been across on ropes) and slopes towards the sea, so that as you get closer, they disappear from view.

The Birrier of West Sandwick, Yell, faces the Kame of Isbister across the water. Access via a rocky ridge is almost as dangerous as that to the Kame. Both sites have a bank on the landward side of the stack, giving the impression that the people there wanted to cut themselves off from the world.

The Birrier of West Sandwick, Yell, faces the Kame of Isbister across the water. Access via a rocky ridge is almost as dangerous as that to the Kame. Both sites have a bank on the landward side of the stack, giving the impression that the people there wanted to cut themselves off from the world.

The official Core Path to Fethaland follows the coastline. For a shorter, less boggy, walk, it is possible to cut across the field from the stile. Head north-west to join the substantial track to the lighthouse, using the gate in the corner of the field.

Follow the track north to the Haaf Fishing Station at Fethaland (HU 375 943). Around 60 boats were based here from the mid-18th century to the end of the 19th century, operating out of 36 stone-built fishing lodges, many still standing to roof height. Sixareens (6 oared boats) went up to 50 miles out, to the continental shelf (the Far Haaf). Boats were at sea for 36 hours at a time, twice a week, between May and August. Younger boys stayed ashore to spilt the cod and ling open and dry them on the beach. Idyllic as Fethaland appears in the sun today, the buildings stand testament to a time of oppression and danger, when the lairds forced the men to fish regardless of the weather. On occasion, when a boat was lost due to storms, the widow was charged for the loss of the boat. Meanwhile, back at home, the women dealt with all the summer croft work.

Follow the track north to the Haaf Fishing Station at Fethaland (HU 375 943). Around 60 boats were based here from the mid-18th century to the end of the 19th century, operating out of 36 stone-built fishing lodges, many still standing to roof height. Sixareens (6 oared boats) went up to 50 miles out, to the continental shelf (the Far Haaf). Boats were at sea for 36 hours at a time, twice a week, between May and August. Younger boys stayed ashore to spilt the cod and ling open and dry them on the beach. Idyllic as Fethaland appears in the sun today, the buildings stand testament to a time of oppression and danger, when the lairds forced the men to fish regardless of the weather. On occasion, when a boat was lost due to storms, the widow was charged for the loss of the boat. Meanwhile, back at home, the women dealt with all the summer croft work.

Just beyond the fishing station, almost on the beach, there is an impressive prehistoric house (see ST 10th April), a well-used picnic spot. From here, continue along the track and at the third electricity pole, turn right to follow a very insubstantial burn. At the coast, look north and all being well, you should be able to see the round bases of bowls which the Vikings prised from the cliffs. Take great care as you have to be fairly close to the edge to see them and soapstone is slippery underfoot when wet.

If you still have the energy, you can head back to the track and further north to the lighthouse or beacon at the end. It was constructed in 1977 to assist shipping from Sullom Voe.

Your return journey can either follow the coast or the track. If you take the track, be aware that there usually is a bull in the field closest to the road (as the signs suggest). I generally go back exactly the way I came, rather than following the track all the way back to the road.

Where else to spot Viking quarries

We have recently realised that there are far more outcrops of soapstone in Shetland than archaeologists had originally thought, although the Vikings were well aware of that. Eileen Brooke-Freeman used place names to find small seams of, previously unrecognised, soapstone all over Shetland. Many of these were almost worked out in the past.

We have recently realised that there are far more outcrops of soapstone in Shetland than archaeologists had originally thought, although the Vikings were well aware of that. Eileen Brooke-Freeman used place names to find small seams of, previously unrecognised, soapstone all over Shetland. Many of these were almost worked out in the past.

Anne- Christine Larson’s excavations at the longhouse at Belmont, Unst found that the floor was littered with chippings from finishing soapstone objects. A lamp, which was nearly completed when it broke, was thrown away in disgust. The soapstone was probably, at least in part, from the hill just above the farm, where there was evidence of several small, worked out, soapstone outcrops.

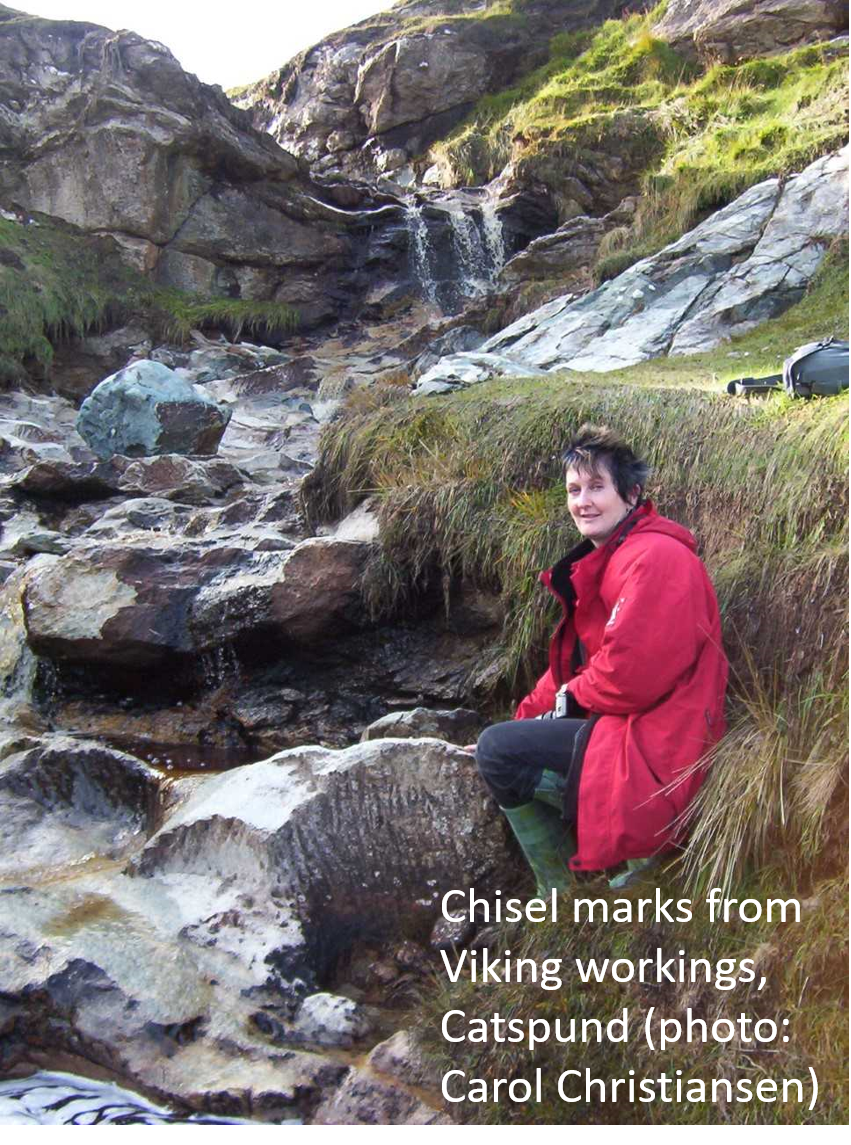

The largest Viking soapstone quarries in Shetland are at Catpund, Cunningsburgh (HU 425 271). Excavations in 1988 demonstrated that they cover an extensive area of the hillside. Although the excavated area was left open, it was partially reburied during peat slips, and now the best place to see the ancient workings is just above a disused loop of the old road, along the burn itself. Iron in the peaty water is gradually staining the grey soapstone to brownish-orange. The bowls were cut out of the rock, working from the open face. The rock left behind shows clear chisel marks, as well as the rounded and rectangular shapes of the removed blocks.

The largest Viking soapstone quarries in Shetland are at Catpund, Cunningsburgh (HU 425 271). Excavations in 1988 demonstrated that they cover an extensive area of the hillside. Although the excavated area was left open, it was partially reburied during peat slips, and now the best place to see the ancient workings is just above a disused loop of the old road, along the burn itself. Iron in the peaty water is gradually staining the grey soapstone to brownish-orange. The bowls were cut out of the rock, working from the open face. The rock left behind shows clear chisel marks, as well as the rounded and rectangular shapes of the removed blocks.

The quarry on the coast below Houbie, Fetlar, (HU 618 903) appears to have been a very organised operation, and may be rather more recent. Blocks of grey-green soapstone were extracted in orderly rows, ensuring that nothing was wasted.

The Vikings quarried an unusual pink steatite at Hillswick. That is one of the places I hope to include in a walk for next week.

Dr. Val Turner, Regional Archaeologist, Shetland Amenity Trust

We hope you have enjoyed this blog.  We rely on the generous support of our funders and supporters to continue our work on behalf of Shetland. Everything we do is about caring for Shetland's outstanding natural and cultural heritage on behalf of the community and for future generations. Donations are welcomed and are essential to our work.

We rely on the generous support of our funders and supporters to continue our work on behalf of Shetland. Everything we do is about caring for Shetland's outstanding natural and cultural heritage on behalf of the community and for future generations. Donations are welcomed and are essential to our work.