What to look for this week - The trouble with lichen

Published: 17 June 2020

The trouble with lichen was a sci-fi book written by John Wyndham – he of Midwich Cuckoos and Day of the Triffids fame. It centres on the discovery of a lichen that can slow down the human ageing process. Anyway, enough of that – the real trouble with lichens is that they are darn hard to identify! The identification features are often microscopic and you need to carry round a bunch of chemicals to test some of them. Not for the faint-hearted and certainly not for me! That said they are fascinating – if you don’t believe me go and look at some with a hand lens or turn you binoculars around and get up close to the lichen and take a look – it’s a whole new world, a bit like Honey, I shrunk the kids.

The trouble with lichen was a sci-fi book written by John Wyndham – he of Midwich Cuckoos and Day of the Triffids fame. It centres on the discovery of a lichen that can slow down the human ageing process. Anyway, enough of that – the real trouble with lichens is that they are darn hard to identify! The identification features are often microscopic and you need to carry round a bunch of chemicals to test some of them. Not for the faint-hearted and certainly not for me! That said they are fascinating – if you don’t believe me go and look at some with a hand lens or turn you binoculars around and get up close to the lichen and take a look – it’s a whole new world, a bit like Honey, I shrunk the kids.

Lichens are literally everywhere in Shetland, all around us. They are actually a partnership of a fungus – which gives the lichen its scientific name and an algae. A symbiotic relationship – one that benefits both participants. The algae produces sugars by photosynthesis and the fungi steals these sugars so that it can grow. In return the fungus provides protection and gathers nutrients and moisture from the environment.

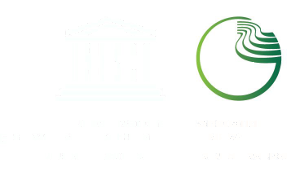

Some lichens have very particular habitat requirements, while others will grow almost anywhere that is suitable. Most Shetland lichens grow on rocks – it’s not uncommon to find a rock face entirely covered with lichens – although which species grow on any particular rock face will depend on the chemistry (geology) and physical hardness of the rock. This can be well illustrated by taking a walk around a cemetery and seeing the different lichen communities that can be found on headstones made from different rock types. The other habitat where lichens are obvious is on trees and shrubs; Shetland is not well endowed with trees but take a look around the older plantations and even some of the newer gardens and lichens can soon be found on tree trunks – sycamore can be particularly good. Finally we have a suite of lichens that grow on peat and soils. The greyish lichens of the genus Cladonia (sometimes known as reindeer lichen) can be especially obvious on heathland that is not too heavily grazed by sheep.

Some lichens have very particular habitat requirements, while others will grow almost anywhere that is suitable. Most Shetland lichens grow on rocks – it’s not uncommon to find a rock face entirely covered with lichens – although which species grow on any particular rock face will depend on the chemistry (geology) and physical hardness of the rock. This can be well illustrated by taking a walk around a cemetery and seeing the different lichen communities that can be found on headstones made from different rock types. The other habitat where lichens are obvious is on trees and shrubs; Shetland is not well endowed with trees but take a look around the older plantations and even some of the newer gardens and lichens can soon be found on tree trunks – sycamore can be particularly good. Finally we have a suite of lichens that grow on peat and soils. The greyish lichens of the genus Cladonia (sometimes known as reindeer lichen) can be especially obvious on heathland that is not too heavily grazed by sheep.

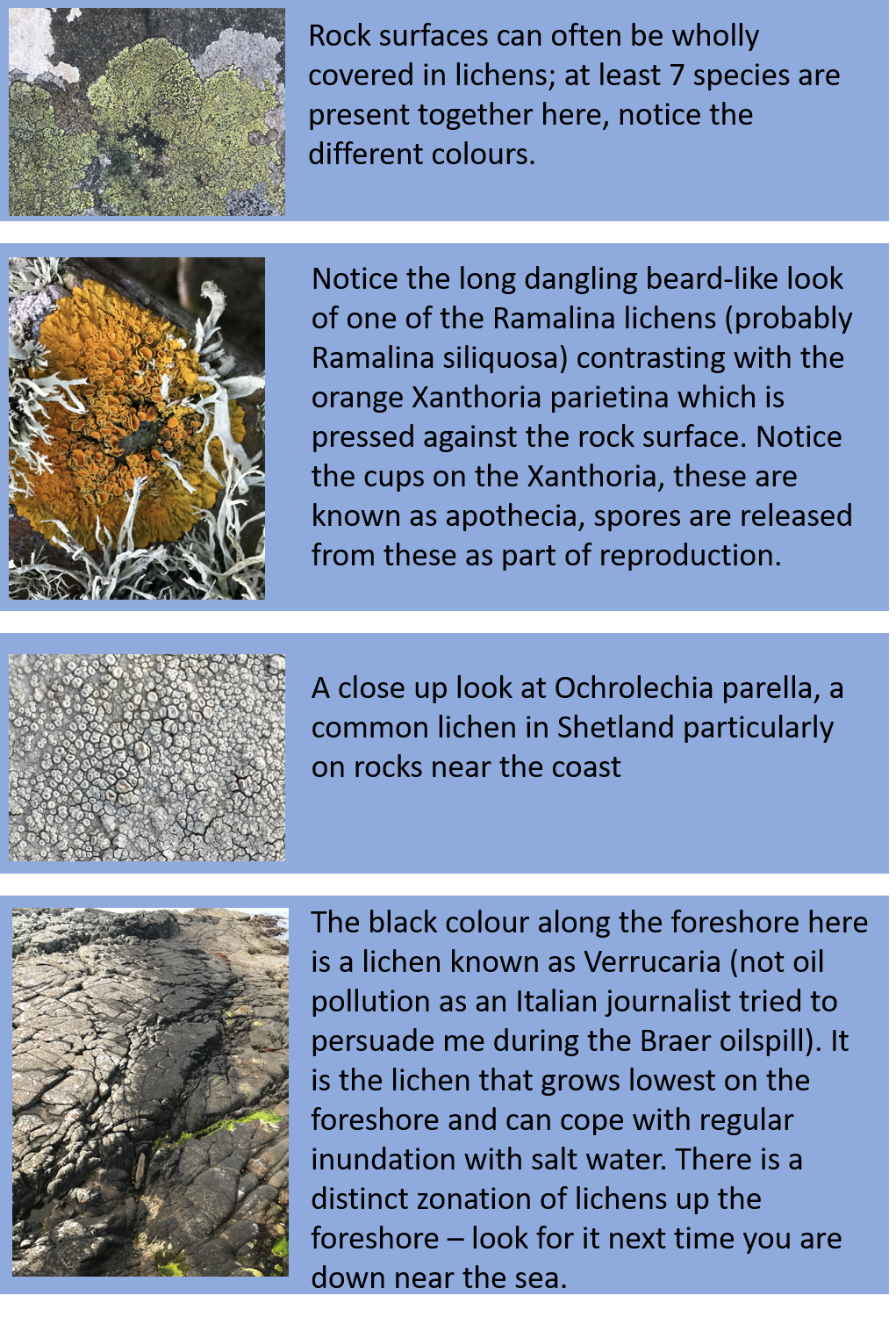

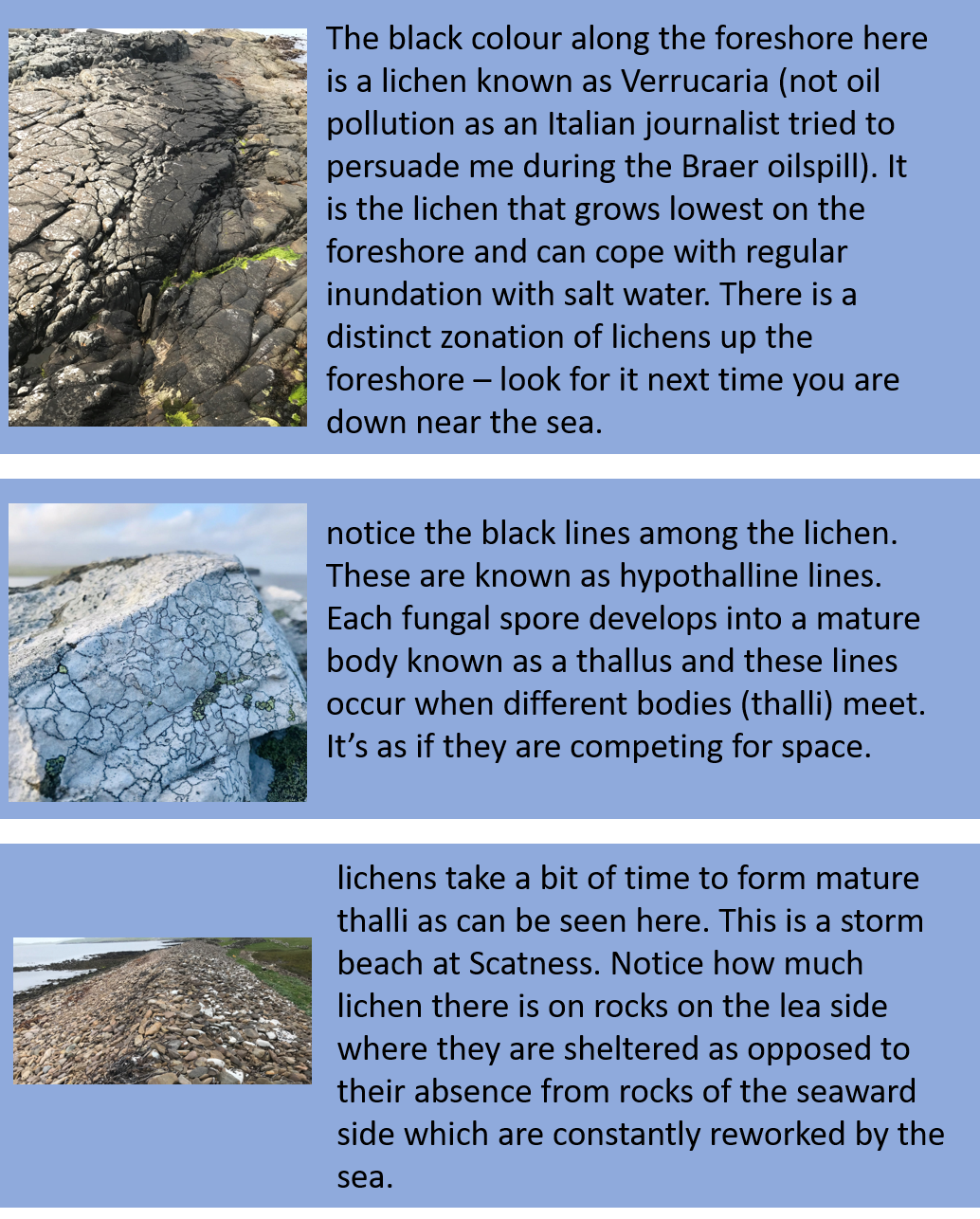

Different lichen species have different responses to air pollution – some will disappear very quickly if gaseous pollutants such as sulphur dioxide are present whereas some species are more robust. So, studies of the lichen flora present in a particular area can give us an indication of air quality at that site. The abundance of lichens in Shetland is an indicator of just how clean the air is here in the islands; among the cleanest in the UK. Of course, lichens have had a more direct use to people than just as indicators of pollution. They have long been used in the dyeing of wool although in recent times man-made organic compounds have largely replaced them – maybe that’s a good thing for the lichens! Some of the species commonly used for this purpose in Shetland are shown in the photographs, Ochrolechia parella, Ramalina siliquosa and the orange Xanthoria parietina.

Paul Harvey, Natural Heritage Officer, Shetland Amenity Trust - June 2020

We hope you have enjoyed this blog.  We rely on the generous support of our funders and supporters to continue our work on behalf of Shetland. Everything we do is about caring for Shetland's outstanding natural and cultural heritage on behalf of the community and for future generations. Donations are welcomed and are essential to our work.

We rely on the generous support of our funders and supporters to continue our work on behalf of Shetland. Everything we do is about caring for Shetland's outstanding natural and cultural heritage on behalf of the community and for future generations. Donations are welcomed and are essential to our work.