Off the Beaten Track 19 – Skaw

Published: 06 August 2020

Archaeology encompasses everything which is part of the current pattern of land use. This means that, surprising as it may seem, military remains count as archaeological sites. Of all Shetland’s military remains, the most coherent and extensive are in Skaw, Unst, where RAF Skaw has survived intact. Todays walk takes in these impressive military remains, steps back in time to view a Viking longhouse and, if you take your binoculars, at the right time of year, you might even spot phalaropes or an ORCA.

Shetland’s position, between mainland Europe to the east and the Atlantic to the west, gave the islands a strategic importance. RAF Skaw (HP 666 154) was established in 1940, following the German invasion of Norway. The intention was to provide early warning reports for the overall air and sea defence of the nation, particularly given the now increased possibility of a German invasion through Norway. It formed a key part of the Chain Home radar network, a series of early warning radar stations first developed in the 1930s and laid out along the coastline of Britain.

Construction at Skaw took twice as long as many mainland counterparts because of the extreme conditions and remoteness of the location. Over 15,000 tonnes of material were transported by sea and landed at Haroldswick to build the complex, which was the northernmost site of the Chain Home network.

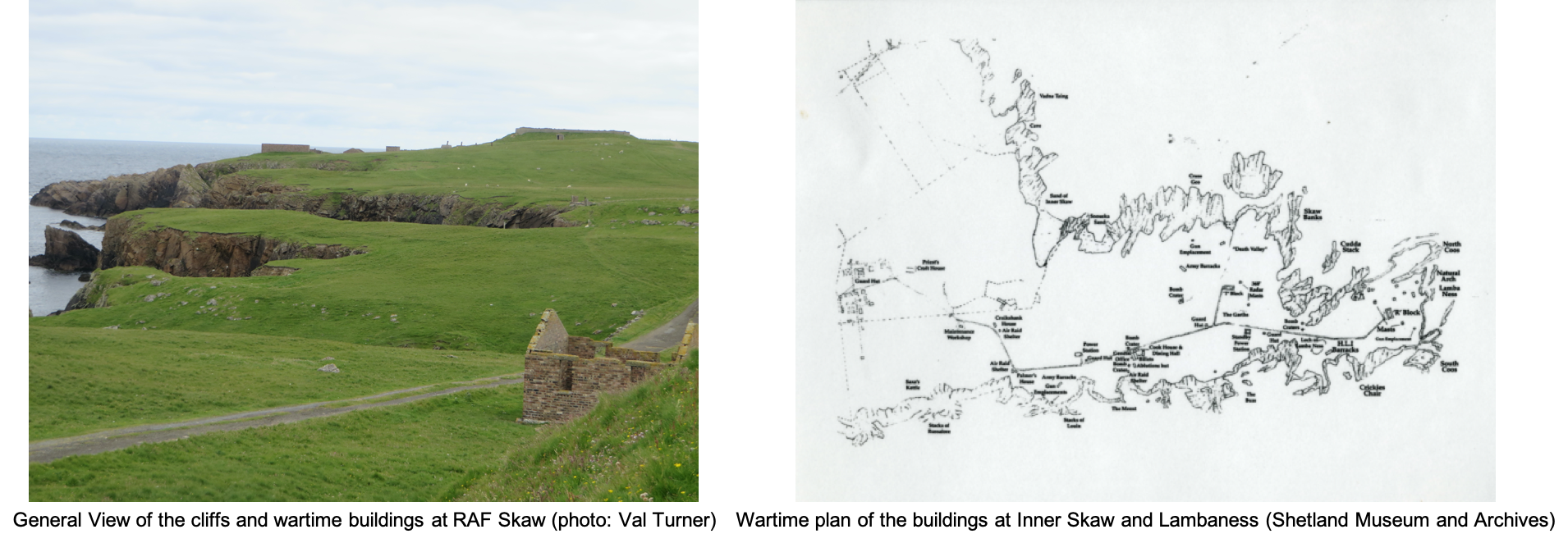

The main site at Skaw extends from Inner Skaw to Lambaness, an area about 2 kilometres long and nearly half a kilometre wide at its widest point. It has recently been earmarked as a suitable site to create a satellite launch space station. As a result, archaeologists are currently working to ensure that, should the development go ahead, the site will still remain intact and as impressive as it is at the moment and that people will be able to visit it, apart from the brief periods when the launch pads are in use of course.

There were 17 radar stations built in Scotland. By the end of 1945 there were over 300 sites across Britain. RAF Skaw is an exceptionally well-preserved example, scheduled (protected in law) as being a site of National Importance.

Their primary function was to alert the military authorities of the position, course and speed of any approaching aircraft for a distance of up to 100 miles. RAF Skaw could not, however, detect low-flying or seaborne targets. Ten sites were added to the chain, including both Saxa Vord and Sumburgh Head, to ensure that lower targets were not missed. This was known as the Chain Home Low system.

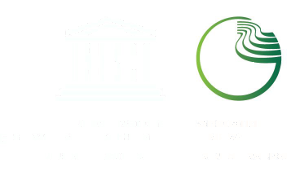

The Skaw peninsula was selected for its north-easterly position and its height, which provided a well-protected and extensive radar range. The site was vulnerable from the air but the peninsula was almost surrounded by steep cliffs. The one small beach was blocked with metal posts which were stuck vertically into the sand.

The extensive complex includes a variety of concrete and brick buildings and structures, some of which are heavily protected with blast walls. The bricks were manufactured by ETNA and Edinburgh brickworks and imported into Shetland. The radar station only ever had a short lifespan, during World War Two.

For a largely flat walk of about 4 kilometres around Skaw, park near the Interpretive Board. The first group of buildings which you encounter (centred on HP 657 156) was the officers’ domestic area. These buildings are the most ruinous part of the site. They survive largely as the lower courses and foundations of individual buildings and concrete pads marking out the outlines of buildings. In addition to the officers’ accommodation, they included ammunition stores, bathrooms, the cookhouse, air raid shelters, a medical block, garages for vehicles, a cinema and even an outdoor boxing ring. Anchor points, used to secure the roof structures against extreme weather conditions, are still visible. The decontamination block is still roofed.

The next stop on the walk takes you back about 1,000 years. To find it, continue along the military road to just beyond the cattle grid. The site lies on the north side of the road, situated in the valley of a small stream which runs down to the, later fortified, sandy beach.

Vikings at Inner Skaw (HP 663 156)

There is a long-lived series of houses here. The earliest is probably a Viking longhouse, the latest was probably used up until the nineteenth century. The recent croft building nestles amongst the walls of several rectangular structures. To find the longhouse, look for the grass-covered footings underneath the croft buildings. The remains survive best inside the later enclosure. The longhouse is aligned down the slope and is divided into three rooms. The walls appear to be slightly bowed, and this together with the dimensions lends weight to the interpretation of the longhouse as being Viking.

The series of abandoned fields around the buildings belonged to various phases of the settlement, created over a long period. On the northwest side of the stream, crofting period fields survive as narrow strips, now marked by lynchets (drops in slope) on the hillside. These terraces may have been created deliberately, as opposed to being the result of soil creep.

Gun emplacements and barracks

Continuing east, the second group of wartime buildings, to the south of the track, includes the army barracks and buildings used by the ordinary RAF workforce. On average there were around 150 men living at Skaw at any one time. The most southerly structures in this group were the gun emplacements, intended to protect the complex. The bomb craters further down the peninsula suggests that they weren’t entirely successful.

Receiving and Transmitting

As you continue to end of the peninsula, the buildings become more dispersed and are exceedingly well-preserved. These were the technical buildings and structures - the receiving and transmitting masts and buildings. The masts stood over 100 metres tall. The processing rooms were heavily reinforced to ensure that they survived any direct hits from airborne ordnance. Although only the metal anchor points and concrete plinths survive from the masts, the transmission block and the receiving block, which is the building furthest to the east, survive largely intact with several of their fixtures still in place. The small neat brick buildings on the tip of the peninsula were added a year or two after the main construction.

Blue Jibs, the Reserve Site (HP 663 168)

Before you leave the area, why not drive a little further north to the reserve site at Blue Jib? This was far smaller and only included the essential components for transmission, reception and defence. It has a very compact footprint, approximately 200m long by 200m wide.

Dr Val Turner, Regional Archaeologist, July 2020

We hope you have enjoyed this blog.  We rely on the generous support of our funders and supporters to continue our work on behalf of Shetland. Everything we do is about caring for Shetland's outstanding natural and cultural heritage on behalf of the community and for future generations. Donations are welcomed and are essential to our work.

We rely on the generous support of our funders and supporters to continue our work on behalf of Shetland. Everything we do is about caring for Shetland's outstanding natural and cultural heritage on behalf of the community and for future generations. Donations are welcomed and are essential to our work.